THE NEED FOR SOMETHING OTHER THAN ARREST

Researchers and practitioners often call jails in the United States “the new asylums” for the rising number of individuals they confine with behavioral health needs and substance use disorders. Some calculations estimate that nearly 20 percent of individuals confined in jails have a severe mental health diagnosis (SMHD) and nearly 65 percent have a substance use disorder (SUD). To reduce jail populations for individuals with treatment needs, many police departments issue written citations for certain offense types and situations instead of arresting the person and booking them in jail. These “citation in lieu of arrest” programs help reduce the jail population; however, they still involve the formal criminal legal system instead of engaging support from community-based services. Fortunately, police departments in Pima County, AZ and Charleston County, SC critically examined their role and how their arrest practices contribute to the unnecessary jailing of individuals with severe and co-occurring mental and behavioral health needs. In a 2020 interview with The Philadelphia Citizen, then-Tucson Police Department (TPD, Pima County) Chief Magnus reflects on TPD’s historic arrest-only practices for these residents,

“We’re really trying to develop the resources and do some cultural change around the idea that arresting people or chasing them down is a measure of success and should be celebrated. We’ve moved away from that.”

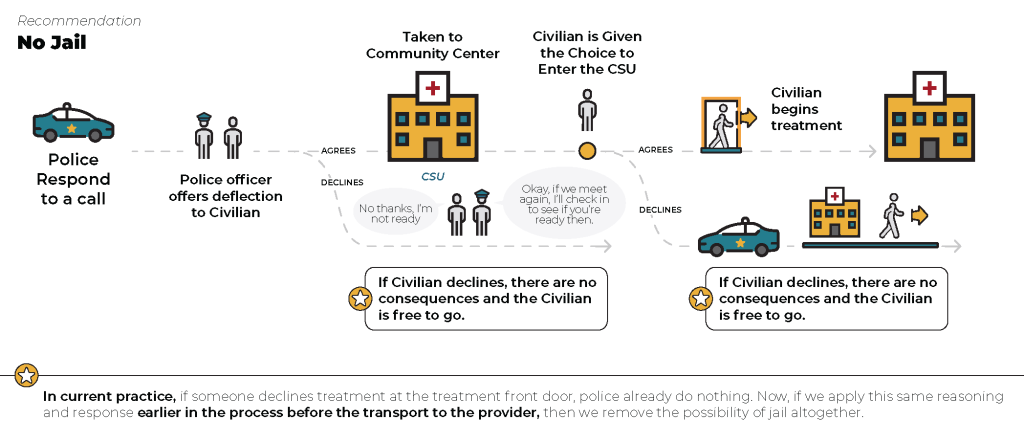

POLICE-LED DEFLECTION

Police departments are moving away from arrest-only practices and focusing on police-led deflection. With deflection policies, police can offer the individual the opportunity to go to a crisis center or treatment center and avoid a citation or an arrest completely. If an individual agrees, the officer drives them to the community provider where a staff member meets the individual and police at the door, known as a “warm handoff.”

Once the person arrives to the treatment provider and if the individual chooses not to enroll in the program, they may leave and there is no legal consequence to the individual. This option allows police to replace jail with direct behavioral health services for individuals with complex needs while eliminating the legal system involvement altogether. It allows individuals the opportunity to enter the treatment open door while completely exiting the criminal legal system’s revolving door. This approach helps redirect or deflect individuals to get the help they need.

POLICE-LED DEFLECTION IN PIMA & CHARLESTON COUNTIES

Importantly, Pima and Charleston counties continue to deflect individuals to these services, regardless of if an individual received a deflection in the past, which reflects what we know about starting treatment – the need for multiple opportunities to start. Although a true behavioral health approach to mental health and substance use crisis would remove police from the interaction completely, currently many cities and counties cannot remove police from the equation – funding, personnel, logistical and legal transport concerns all keep police as one of primary responders. If police must be involved in crisis events, then police-led deflection programs provide a lot of benefits to both individuals and the criminal legal system. It helps police by returning them to the street or 911 queue more quickly. It also impacts jails by redirecting individuals who require intensive and costly services and care while confined during the pretrial phase to community programs better equipped for their needs. For jurisdictions where police continue to respond to services, expanding these police-led programs is important to both decarceration strategies and helping people get the services they need. Understanding the effectiveness of these programs and how police make decisions about who and when to deflect is important to these expansion efforts. As a result, we teamed with Pima County, AZ and Charleston County, SC counties to ask two main questions:

1. How does deflection to a local crisis center impact future arrest and/or continued access to the crisis center?

2. How do police make decisions about who and when to deflect individuals to these crisis centers?

A REDIRECTION FROM THE CRIMINAL LEGAL SYSTEM REVOLVING DOOR TO THE TREATMENT OPENING DOOR

Studying the programs in both Pima County, AZ and Charleston County, SC revealed police are making arrest and deflection decisions all day, every day. Police make these decisions informed by:

-

- Why they were called to the scene;

- If the offense or situation is eligible for deflection;

- Mental state of the individual;

- Cooperation of the individual;

- The time of day they were called;

- How a victim or business owner wants to proceed, and;

- If an individual wishes to begin seeking help.

Any combination of these factors impacts whether a police officer offers the individual a deflection or relies on arrest. At times in these two sites, when police offer deflection to individuals, individuals might not enroll in the program once they arrive at the center’s front door. Other times, an individual might enroll but leave the center early. In either case, police do not consider this failing treatment or a failed deflection. Rather, police from Pima and Charleston understand these experiences are part of the treatment initiation and engagement process, and consistent with what we know about how people get well. As a result, police in these counties continue to offer the same people multiple opportunities for deflection. The need for multiple opportunities to start treatment reflects the treatment evidence which states the reasons people decline treatment is complex and varied, and multiple opportunities to engage overtime can help. Therefore, continuous deflections are more efficient overtime, reduce reliance and cost on the jail, and continue to offer opportunities for- and direct access to treatment. Each time police offer another deflection to an individual, they provide the individual direct access to the treatment open door while keeping them out of the legal system’s revolving door.

THE TREATMENT OPEN DOOR

A treatment open door is a positive parallel process to the legal system’s revolving door. Treatment initiation and engagement is complex and there are both individual concerns and broader system concerns individuals navigate that make starting and continuing treatment very hard. This study with Pima and Charleston Counties revealed the critical need to keep individuals with severe needs out of jail and the legal system. However, in both counties, police do not always offer deflection – even if they’ve offered it to that individual before or under similar conditions. The study revealed at times, police may arrest an individual – even when they recognize jail is not helpful for the individual. We believe if police must continue to respond to crisis calls and use deflection programs, there are two critical principles police must incorporate into their deflection policies: (1) deflection as the primary response and (2) deflection for all, if at all. These principles ensure individuals have access to the treatment open door and ensures this access is not conditional or contingent.

POLICE AS FRONTLINE EDUCATORS

Officers in both counties considered many of the same factors when deciding between deflection and arrest including the extent of physical harm to others and if individuals agreed to the deflection. Importantly, in both counties, even when officers recognized arresting the individual would not help them, they still choose to do it when a victim requested it. This means victims have a lot of say in whether individuals gain immediate access to the treatment open door. However, if we consider police as teachers and educators in these moments, they can educate victims about why deflection to treatment services is more productive and, ultimately safer, for everyone. This opportunity means police act as community educators. If police do not take advantage of the opportunity to educate the victims in these situations, then we risk victims’ implicit/explicit biases impacting which door people are offered and if people can get the help they need.

KEY FINDINGS

- Deflection-first, arrest-rare as both policy and principle connects vulnerable individuals to the services they need while eliminating the collateral consequences of the legal system.

- A parallel treatment open door to the legal system’s revolving door does not suggest failure on any individual to initiate or complete treatment, or a failure of deflection.

- A parallel treatment open door, at the very least, provides individuals with SMHD or SUD a “no wrong door” policy, while creating enhanced opportunities for treatment and eliminating the collateral consequences of the legal system and jail.

- The ability to deflect the same individual more than once means police hold an incredible amount of decision-making power for triaging people out of the legal system revolving door and into a treatment system open door.

- When agencies distance themselves from jail and deflect as the primary response, and do so for all individuals, they no longer make access to the treatment revolving door conditional or contingent.

- Understanding how deflection programs work in practice and how police make decisions about who to triage out of the legal system is key to improving and expanding these programs, reducing jail populations, improving equity and access to care, and helping individuals get the help they need.

RECOMMENDATIONS

When police agencies begin to dismantle core practices that funnel individuals into the legal-system revolving door, they begin to distance their communities from experiencing the incredibly harsh and violent consequences of incarceration. And, when police agencies do this for all individuals, then they no longer make access to the treatment open door conditional or contingent. It lessens opportunities for implicit or explicit bias, determinations of worthiness, and non-clinical judgments about readiness for change to impact the help someone can receive, and ultimately enhancing equity in the process.

In this way, a (1) deflection as the first response and (2) deflection for all, if at all, recasts police as important and critical gatekeepers to treatment services. It also elevates police agencies as perhaps the single most important legal system actor for creating spaces to increase equity earlier in the process. To learn more, click here for the full report.

JSP Direct To Your Inbox

Get the latest news and articles from JSP.